It's not an unusual question: How long does it typically take to get a patent?

Unfortunately, even with recently implemented systems to expedite the process, it can still be years before an application is granted a patent. Just look at the case of Drs. Frank Hurley and Thomas Wier.

Yes, this is the promised story of their patent saga.

Rice Institute accepted the terms of the offer laid out in Dr. Hurley's letter (see previous post), with little change. Hurley and Wier would provide all necessary documentation and future testing as necessary, and Rice provided all legal and administrative support to become the assignee.

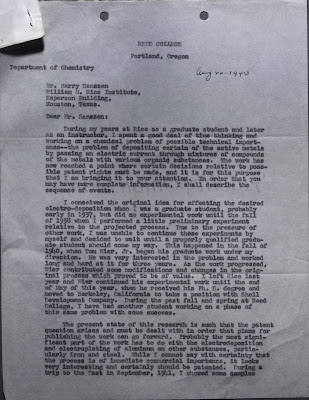

This initial set of correspondence took place in August, 1943. During the remainder of that year, a few key players emerged.

- Dr. Harry B. Weiser (Chemistry Department, Rice Institute): reviewed the research of the two former Owls and consulted on technical matters

- Mr. C. A. Dwyer (Secretary to the President): provided administrative support and facilitated communications

- Dr. Edgar Odell Lovett (President, Rice Institute): generally the top guy in charge--what more can I add about one of the most influential figures in Rice's history and culture?

- Mr. Harry C. Hanszen (Board of Trustees, Rice Institute): Board member known personally by Dr. Hurley, recipient of the August 1943 letter, and namesake of Hanszen College

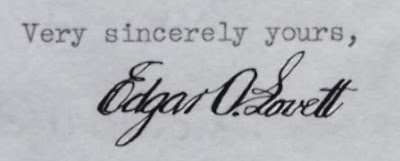

|

| Edgar Odell Lovett's signature |

It's a particularly important list because--aside from the members' roles in shaping Rice and Houston--across the years and correspondence, it can be difficult to keep track of all those involved. Despite industrial interest in the inventions and positive chemistry faculty feedback, the three electrodeposition of aluminum patents were not granted until 5 years later.

Those keeping track of the story likely already noticed the time lag. And those familiar with patents are likely also familiar with a two or three year wait between application and granting. However, over four years between filing applications (February 1944) and granting patents (August 1948) is slightly longer than usual.

Across those four and a half years, the USPTO patent examiner continued to find problems and reject the applications. Evidently, these rejections were not typical. Rice's legal team felt the assigned examiner had "been extremely stubborn in this instance, rejecting the applications repeatedly, though not finally, on grounds not in accordance with the Office practice".

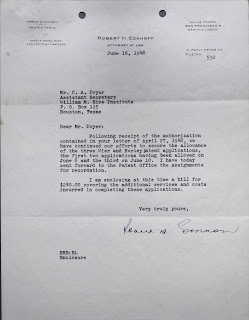

|

| 1947 letter from the attorney office containing the above quote. |

The university Board agreed, and mentioned removing Eckhoff, as Dr. Wier expressed extreme dissatisfaction with how he handled their representation.

In the end, Wier and Hurley were required to run additional tests and submit signed affidavits to prove their processes were unique improvements to prior art. One of the three original applications was completely rejected; a third was then born of one of the other two. These became application serial numbers 524,486 and 542,487, joining 522,387.

An attorney from Eckhoff's firm approached an associate in Washington D.C., who had an inside line to the USPTO Examiner, to attempt to remediate and expedite their applications. This strategy worked; on June 16, 1948, a letter informed Mr. Dwyer the three applications were accepted about a week prior. Unfortunately, I found no record of what transpired during those meetings and/or exchanges.

|

| June 17, 1948 letter of acceptance. |

In the end, what is most frustrating today, is that somehow Rice no longer has the originally issued patent grant certificates. The patent attorney's letters that accompanied these documents was retained in the archives, giving important context to this story; one must wonder what happened with the patents. Perhaps they were presented to the inventors.

Correspondence enclosed in this archival file concludes with licensing the developed technology to several interested companies, proving the original expectations.

The next entry in this series will be the conclusion. It looks at the infancy of a Rice Institute intellectual property policy pursued in relation to the Hurley/Wier patents.