For those who have been waiting in breathless suspense, you’re in luck: this entry is a continuation of the search for the history of Rice’s first patent.

Since the last entry, I have spoken with a few people who had information to share, and some insights into patents at Rice. There was indeed a direct relationship between the patents granted roughly simultaneously with the issuance of new IP policies. Landmark innovations (like processes to isolate fullerenes) during the 1990s probably made clear the need for a strong IP policy and patent strategy.

Most important among recent findings are the three patents issued in 1948 for electrodeposition of aluminum. The inventors listed are Frank H. Hurley on U.S. 2,446,331; Thomas P. Wier, Jr., on U.S. 2,446,350; and both on U.S. 2,446,349.

|

| U.S. Patent 2,449,349 |

I was originally confused by these patents' wording; on contemporary patents, Rice University is identified as the “assignee”. On the 1948 patents, Drs. Hurley and Wier are shown as “assignors to” Rice Institute. The uncertainty stemmed from whether or not this would mean the patents were issued for something created on Rice’s behalf, while employed by or studying at Rice, or if ownership was later transferred.

Furthering this confusion is the history of the two inventors.

Frank H. Hurley earned his bachelor of arts (chemistry) in 1932 and his chemistry PhD in 1936 from Rice Institute. Going by papers found in the Digital Scholarship Archive, Dr. Hurley was a chemistry instructor at Rice for several years; but moved to Reed College by 1942. The move explains why his location on the patents was in Portland, Oregon; it doesn’t explain why he was named along with Rice.

Why? Because that doesn’t line up with information on the other inventor.

Thomas P. Wier earned his materials science engineering PhD from Rice Institute in 1943, and his dissertation title might look familiar: The Electrodeposition of Aluminum.

Well, that would have settled it, if Dr. Thomas Wier was the only inventor, or he earned his degree a few years earlier when Dr. Hurley might have been a faculty advisor. But the patent applications were filed in 1944 and granted in 1948.

I decided to chase down some archival material from both the Woodson and Reed College's collections. Hopefully, some letters between colleagues, patent applications, departmental memos, or anything might hold a few clues.

Reed's archives provided a great deal of background on Dr. Hurley's early career investigations into molecular weights. Unfortunately, none of this appears to be directly related to the electrodeposition of aluminum.

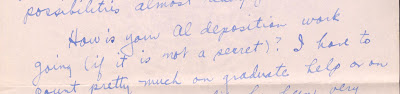

One letter from colleague William Sandstrom in 1942 asks how Hurley's aluminum deposition work is progressing, "if it is not a secret". Reed has only the letter Hurley received, not his response, which dampens the excitement of seeing that line. But the letter was addressed to Hurley at Rice Institute--so it seems he had started the research before leaving for Reed.

| ||

| Asking Hurley about potentially secret aluminum deposition work. |

Basically, there wasn't much in the Reed College archives.

The story of the findings from the Woodson, however, will be discussed in the next exciting post! Stay tuned for the end of this saga, and to learn about three patents from the 1940s.