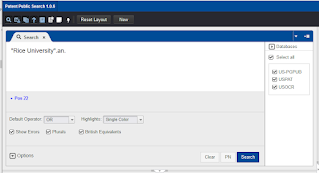

It's finally time to answer the big question about the three 1948 patents, invented by Drs. Frank Hurley and Thomas P. Wier, Jr., and assigned to Rice Institute:

Did the inventors simply assign ownership of the patents to Rice, giving it to an uninvolved Institute independently, or was Rice the home and supporter of the research leading to the patented inventions, and thus an owner (assignee) in the same way Rice is today?

Yes. The answer is yes.

Over several months and across consultations with various Rice and USPTO entities, I found little to provide a definite answer. Additional archival research on the history of the Kelley Center and Fondren as a patent depository seemingly exhausted the potential sources of related records. In desperation, I requested more archival materials like offprints of Dr. Hurley's publications (in hopes of finding some research preceding the patents), and the correspondence of Dr. Wier. A few items from Thomas Wier, Sr., popped up, and were equally as unhelpful.

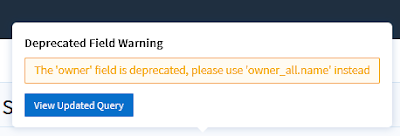

Finally, among the correspondence of Rice Institute president Dr. Houston I found a file labeled "Patents". Fully expecting this to be futile--perhaps about patent investments or something unrelated--I left it for last.

|

A very young Frank Hurley, from the 1932 Campanile

|

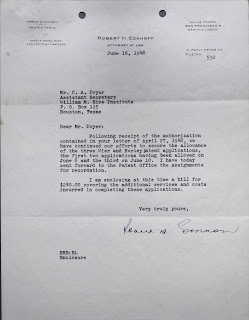

It was surprising yet frustrating to discover that the physical folder was given a much longer title than "Patents", displayed in the finding aid. It specifically named Drs. Hurley and Wier! (I don't blame anyone for that; no one could expect the details on a very long label to be a key piece of information in a future search.) Thus, hundreds of documents have been hidden away for years, decades even, unknown to any PTRC representative or patent librarian, given the lack of recognition and exclusion from the institutional repository, Rice Digital Scholarship Archive.

Here, at long last, was the evidence that could solve the patent mystery, and answer the big question of assignee/ownership and Rice's involvement.

The answer lay in the earliest correspondence document. Yes, the patented inventions were based on research performed at Rice, for Rice scholarship. And yes, the patents were gifted to Rice by Wier and Hurley.

It's a case of both being true. Dr. Hurley started his research into electrodeposition of aluminum while employed by Rice; evidently he was unable to actively pursue it until Wier became his graduate student lab assistant. When Hurley left for Reed, Wier took over the project entirely. As noted in a previous post, this formed his thesis dissertation.

|

An equally young Thomas Wier, from the 1940 Campanile

|

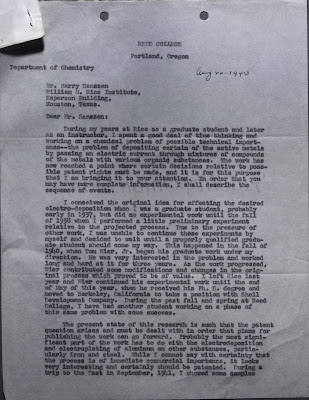

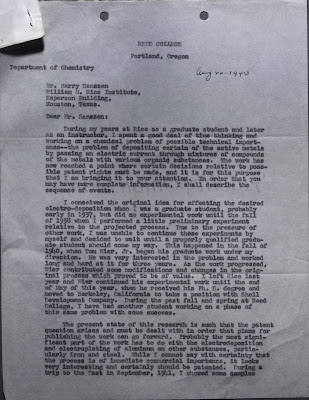

In August 1943, Dr. Hurley wrote to Harry Hanszen. He suggested that their research on the electrodeposition of aluminum may have some commercial value, and proposed that patents for the process should be sought and ownership assigned to Rice. Unlike today, Rice did not seek out formal ownership of intellectual property.

Highlights of the very long missive include:

"My own attitude (and Wier's also, I believe) is that as an alumnus of Rice--a recipient of its educational training and the advantage of its scientific facilities--the Institute can rightly be said to possess some interest in this process."

"As you probably know, several universities have in recent years administered patents assigned to them with great success."

"For my own part, I can say that my principal interest lies in obtaining the recognition which may derive from the publication of this work, for I have cast my lot with the universities and colleges and am anxious too attain to success as a teacher, researcher, or administrator. Should the process prove to be of value, it is my desire that the Institute should receive the greater part of any income deriving therefrom."

|

Dr. Hurley's letter to Hanszen.

|

To read the whole letter (which I recommend, as Hurley crafts a better narrative than I), click here.

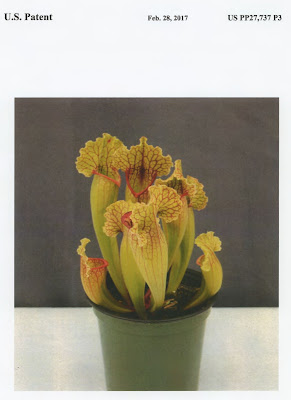

In celebration of solving this mystery, I've officially added the three

patents to Rice's Digital Scholarship Archive, rectifying their previous omission. Check out Electrodeposition

of Aluminum: US 2446350A, US 2446349A, and US 2446331A.

But the tale of Rice's first foray into patent ownership hardly ends there!

The documents revealed many other stories, some to be told another day; look forward to future posts on the saga behind obtaining the patents, the earliest attempts to develop a concrete intellectual property policy, and hopefully the Reed College perspective, once access to their full archives is restored.